Charting Broadband Connectivity for Anchor Institutions

Alexander Gamero-Garrido, an assistant professor of computer science at the University of California, Davis, has begun a new project measuring the strength and availability of broadband networks at community anchor institutions, or CAIs, like schools and libraries.

With funding from the National Science Foundation, Gamero-Garrido and his project collaborators from Northeastern University and UC Santa Barbara will assess, model and analyze the network connectivity and performance at these crucial institutions to better ensure access to the internet for all.

The Great Internet Divide

The idea of the project was sparked nearly five years ago when Gamero-Garrido was struck by a new understanding of the digital equity gap.

It was during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic when schools and libraries shut down and people had to support work and school on their home internet. Reports showed students doing their homework in McDonald’s and Taco Bell parking lots to use the Wi-Fi because they didn’t have reliable internet at home, nor did they have a CAI like a school or library to get access.

“It made me realize that there’s a large group of people in the U.S. and the world that experience the internet very differently from me,” said Gamero-Garrido. “I often thought of the digital equity gap in terms of how to navigate a website or identify resources. I hadn’t thought about the possibility that there’s just no internet at home. That’s an entirely different kind of network interaction that doesn’t get much attention.”

Minding the Gaps

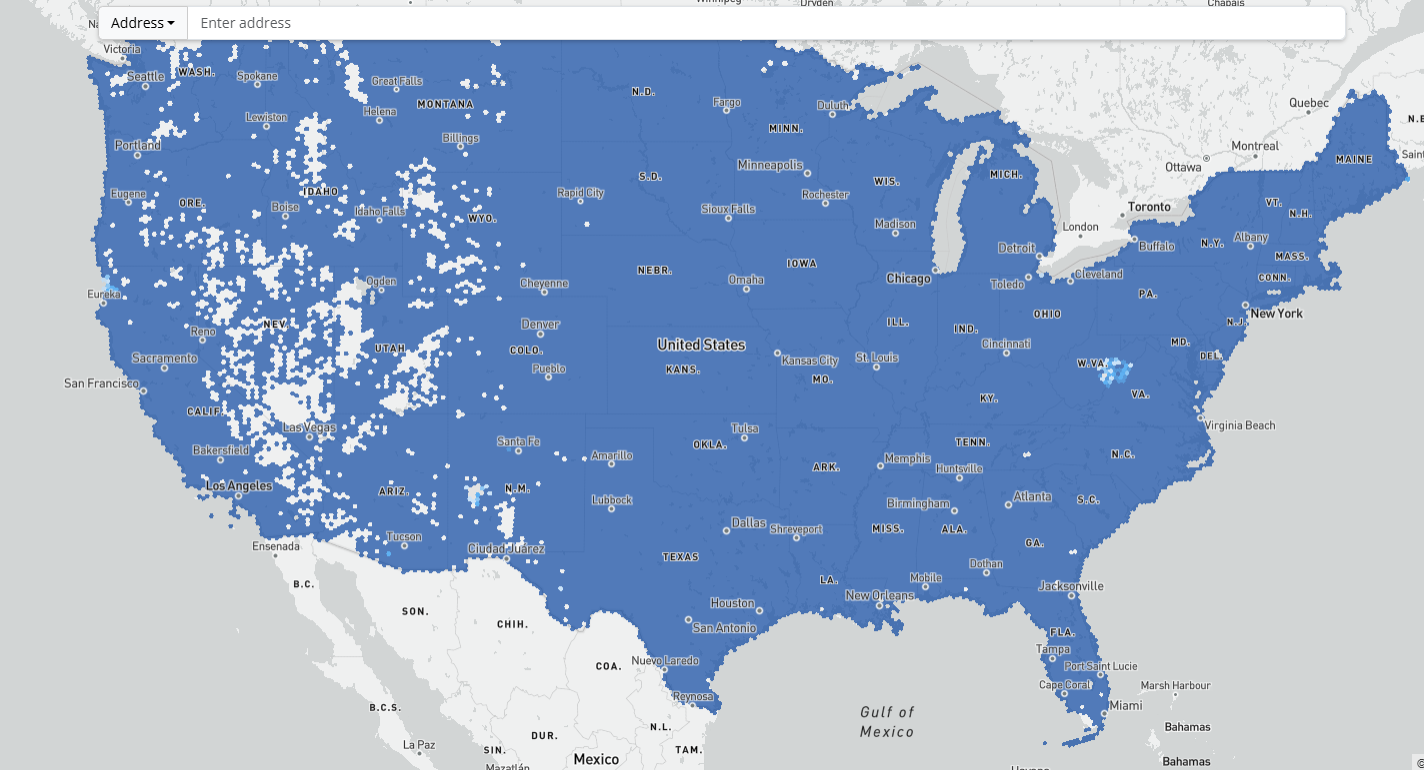

The project aims to achieve three goals. The first relates to network availability: create an annotated map of anchor institution networks, or AINs, including the providers they use to connect to the internet.

Currently, the Federal Communications Commission, or FCC, has a national broadband map that annotates broadband coverage for residents and businesses, which keeps broadband providers accountable to their constituents. For instance, if a provider, like Comcast or Verizon, says they provide coverage to an area and a resident or business has poor or no connectivity, the user can submit a challenge to the FCC. The provider must then work to provide service or revoke their claim in that area.

Until very recently, CAIs have been left off this map — according to Gamero-Garrido, the FCC claimed that CAIs were getting their internet from different networks. This means broadband providers have not been held to the same standards of providing network availability to these institutions.

“[With mapping], we would show the FCC that the providers serving these institutions are just the usual providers,” said Gamero-Garrido. “Then they would be treated in the same way as residences — anchors could file a complaint and resolve their dispute through the process the government has created.”

The other two goals are related to network reliability and network performance: The team will collect evidence to assess how reliable AINs are (i.e., how often they experience outages) and determine whether AINs meet the technology needs of the users (i.e., whether the connection speed is high enough to support multiple patrons’ videoconferencing).

The Tech Toolbox

To achieve these goals, Gamero-Garrido and his team are using conventional measurement tools like traceroute, a diagnostic tool that pinpoints the routers that take a packet (or unit of control information and user data) from one destination to another.

“There are content delivery networks like Google and Facebook that access smaller networks like Comcast to get information delivered,” said Gamero-Garrido. “In order to understand how well provisioned a network is, we need to understand this entire ecosystem from the perspective of the anchor institution.”

Speed tests are another well-known tool being used. In some cases, student researchers go into libraries in the designated areas — Yolo County and Boston-Metro for now — and measure how long websites like The New York Times and Zoom take to load.

Gamero-Garrido and his team are also building software to understand the performance of these networks from libraries and designing a tool called reverse geolocation. Forward geolocation is when an IP address is provided, and someone can estimate that IP's physical location. Gamero-Garrido’s team is interested in the opposite of that.

“You start with a physical location, and then you try to find which IP addresses are located in that region,” he said. “Within those IP addresses that are possibly located in that region, you use a combination of computer networking tools to determine whether that IP is, one, actually located there because we don't know, and two, if it belongs to the kind of organization that we're interested in.”

On the opposite end of the technology spectrum, the team will also gather information via a large-scale survey. Libraries will be asked to confirm or provide their IP addresses and what kinds of applications patrons mostly use.

“It’s a combination of understanding the human needs of the system with identifying mechanisms that can determine whether those needs are met without asking more of the libraries,” said Gamero-Garrido.

Reaching the Edge

While the project is starting with a relatively small sample size, the goal is to expand and focus on low-income, rural and tribal areas, which can be difficult to study because the patrons can be hard to reach or they lack an internet connection at home.

For Gamero-Garrido, whose research has been centered on the intersection of the internet and public policy, this project signifies a homing in on his research agenda. In a field that tends to focus on making the internet better, faster, stronger, Gamero-Garrido not only wants to help facilitate safe internet for all but also accessible internet for all.

“Lately, I am paying more of my attention to the groups that are kind of at the edge,” he said. “They are marginalized to the extent that their experience with technology is different from the average person. If someone were to ask me, ‘Why are you doing this?’ I would say, ‘Well, someone should.’”