Big Help or Big Brother? UC Davis Study Reveals Alarming Browser Tracking

What if you could take a large language model like ChatGPT along with you while you browse the internet? It could summarize webpages, answer questions, translate text, take notes, etc. Basically, it would be your own personal assistant.

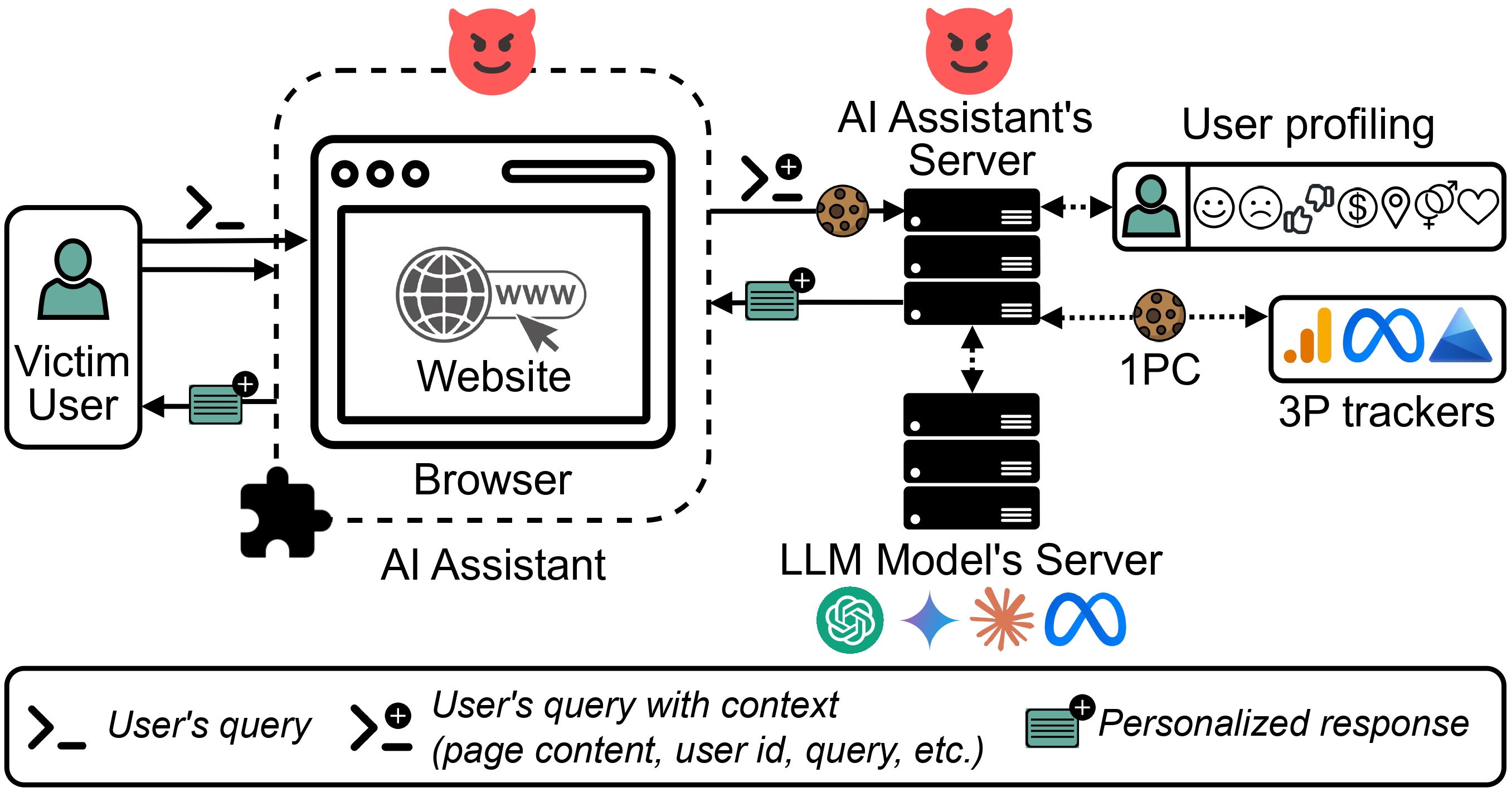

A new brand of generative AI, or GenAI, browser assistants are doing just that. Sold as browser extensions, GenAI browser assistants use large language models to make browsing easier and more personalized, and act as your ride-along as you surf the web.

New research from computer scientists at the University of California, Davis, reveals that while extremely helpful, these assistants can pose a significant threat to user privacy. The paper, “Big Help or Big Brother? Auditing Tracking, Profiling and Personalization in Generative AI Assistants,” will be presented at and published in the proceedings of the 2025 USENIX Security Symposium on Aug. 13.

How Much Does GenAI Really Know About You?

Yash Vekaria, a Ph.D. student in computer science in Professor Zubair Shafiq‘s lab, led the investigation, seeking to answer three questions: Firstly, “How are these GenAI browser assistants designed?” Secondly, “What kind of implicit and explicit data collection and sharing are they doing?” And thirdly, “Are they ‘remembering’ information,” or “Are they doing profiling and personalization?”

To answer these questions, the researchers investigated nine popular search-based GenAI browser assistants: Monica, Sider, ChatGPT for Google, Merlin, MaxAI, Perplexity, HARPA.AI, TinaMind and Copilot, by conducting experiments on implicit and explicit data collection and using a prompting framework for profiling and personalization.

Vekaria and his team found that GenAI browser assistants often collect personal and sensitive information and share that information with both first-party servers and third-party trackers (think: Google Analytics) for profiling and personalization, revealing a need for safeguards on this new technology, including on the user side.

“These assistants have been created as normal browser extensions, and there is no strict vetting process for putting these up on extension stores,” Vekaria said. “Users should always be aware of the risks that these assistants pose, and transparency initiatives can help users make more informed decisions.”

When Private Information Doesn’t Stay Private

To study implicit data collection, Vekaria and his team visited both public and private online spaces — public spaces are sites that do not require any authentication, while private spaces, like sites with personal health information, do. When on these sites, the team asked the GenAI browser assistant questions to see how much and what kind of data they are collecting.

“For example, if it’s a health website, then I log into my health portal, and then go to a page that lists all the past medical visits to a doctor,” Vekaria said. “I navigate to a particular visit where it shows all the historical diagnoses of the patient, the purpose of the current visit, the age of the patient, etc. The assistant is then invoked by asking a benign question about the page, like ‘What do you think the patient’s medical diagnosis is?’”

The team observed that, irrespective of the question, some of the extensions were collecting significantly more data than others, including the full HTML of the page and all the textual content, like medical history and patient diagnoses. Others were only collecting what could be seen on the screen at the time the questions were asked.

One noteworthy (and egregious) finding was that one GenAI browser extension, Merlin, collected form inputs as well. While filling out a form on the IRS website, Vekaria was shocked to find that Merlin had exfiltrated the social security number that was provided in the form field. HARPA.AI also collected everything from the page.

“Users should understand that when they are using assistants in a private space, their information is being collected.”

- Vekaria

Vekaria was pleasantly surprised to see “unique” behavior of Perplexity, which performs a server fetch, meaning Perplexity’s own servers, not the user’s browser, receive the URL of the page, make the HTTP request, receive the page content and process it to answer the user’s question. In this way, Perplexity’s server is not logged in as the user; only the user’s browser is logged on, and if the page is private, the server fetch will get an unauthenticated version of the page.

“Perplexity always enforces this check to prevent any collection of sensitive information,” Vekaria said. “It was the most private assistant we found in our study.”

Building a Profile the GenAI Way

Next, the team looked at explicit data and whether the GenAI browser assistants were remembering information for profiling through a prompting framework using the persona of a rich, millennial male from Southern California with an interest in equestrian activities.

Asking questions to the browser assistants and visiting websites through the lens of this highly specific persona facilitated very specific answers from the GenAI browser assistants.

“Let’s say you open ChatGPT and you ask it, ‘What are three activities that you’d recommend to me if I’m going on a trip?’ It will typically suggest activities like hiking or having a nice dinner,” Vekaria said. “We wanted our profile to be narrow enough that whatever responses we get from these assistants cannot be attributed to randomness.”

To achieve this, Vekaria’s team would visit webpages that supported — or leaked —certain characteristics of the persona in three different scenarios: actively searching for something, passively browsing pages and requesting a webpage summary. In these scenarios, after leaking the information, they asked the GenAI browser assistant to act as an intelligent investigator and answer yes or no questions.

“For example, if we are leaking the attribute for wealth, we would go to old vintage car pages, which have cars worth hundreds of thousands of dollars listed, to show that we are rich,” Vekaria said. “We browse about 10 pages, and then ask the test prompt, ‘Am I rich?’”

In the summarization scenario, the team visited pages and had the assistants summarize each page as they browsed. At the end of each scenario, they asked questions — both in and out of context — to see what the GenAI browser assistant remembered from the leaked information.

“Say, I’ve opened a tab in the browser, I am leaking information, and I’ve asked a set of questions. It’s uncertain if that information is also accessible to the assistant in a new tab, so we ask the same questions again in a new tab to understand if it’s remembering stuff from the other tab. We then ask the vacation personalization prompt: ‘Suggest three activities I should do on vacation.’ Our hypothesis is that it suggests activities like horseback riding or polo that are related to our browsing activity.”

Beyond the Browser Window

Much like the collection of implicit information, some of the GenAI browser assistants, like Monica and Sider, collected explicit information and performed personalization in and out of context. HARPA.AI performed in-context profiling and personalization, but not out of context. Meanwhile, TinaMind and Perplexity did not profile or personalize for any attributes.

Vekaria points to a particularly interesting — and potentially harrowing — finding. Certain assistants were not just sharing information with their own servers but also with third-party servers. For instance, Merlin and TinaMind were sharing information with Google Analytics servers, and Merlin was also sharing users’ raw queries.

“This is bad because now the raw query can be used to track and target specific ads to the user by creating a profile on Google Analytics, and be integrated or linked with Google’s cookies,” Vekaria said.

HARPA.AI and MaxAI were also observed to send information to mixpanel.com, a third party that conducts “session replays,” meaning it records everything the user does on the screen, like where the cursor is moving, and reproduces that information at its servers.

It Takes a Village to Guard Your Privacy

Based on the findings that GenAI browser assistants pose significant privacy risks, the researchers posit that addressing these risks is not up to one singular entity. It will require effort across the GenAI ecosystem.

Developers could be the first barrier to entry with something like keyword-based lists, in which the assistant would avoid collection of data if the web page had keywords like “cancer” or “health.”

Extension stores could play their part in privacy protection with labels on certain extensions that inform the user about potential privacy risks and third-party affiliations. Browsers could offer on-device large language models that browser assistants can use. Regulators like the Federal Trade Commission can establish guidelines for developers, browser vendors and AI model providers, and commit to stronger enforcement of existing privacy laws.

Ultimately, users need to be aware of the risks so they can make the most educated decisions when using these assistants. Vekaria’s ultimate recommendation, however, is to be informed and proceed with caution.

“Users should understand that any information they provide to these GenAI browser assistants can and will be stored by these assistants for future conversations or in their memory,” Vekaria said. “When they are using assistants in a private space, their information is being collected.”

Media Resources

- Jessica Heath, College of Engineering, jesheath@ucdavis.edu

- Yash Vekaria, Department of Computer Science, yvekaria@ucdavis.edu

- Big Help or Big Brother? Auditing Tracking, Profiling, and Personalization in Generative AI Assistants