Student Satellite Project an Exercise in Technology and Teamwork

October Launch to Include UC Davis Payload

This October, if all goes to plan, four graduate students at the University of California, Davis, will see their work launched into orbit. For the past six months, the team at the UC Davis Center for Space Exploration Research has been working with Proteus Space, Inc. on a government-sponsored project to design and build a satellite payload.

“It’s really neat to have worked on something so applied and really have it come to physical fruition,” said team member Jackson Fogelquist, who graduated from UC Davis this June with a Ph.D. in mechanical and aerospace engineering. “It’s pretty exciting and I’d say motivating too.”

The Center for Space Exploration Research is led by Stephen Robinson, a professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering and former NASA astronaut. Associate Professor Xinfan Lin, whose laboratory studies intelligent battery systems, is also taking part in the project.

The goal of the UC Davis payload is to create a digital twin of the satellite’s battery that uses artificial intelligence to predict how the battery will behave in the future.

Adam Zufall, a Ph.D. student in Robinson’s lab, is coordinating the Davis part of the Proteus project. For his doctorate, Zufall is working on an inspection satellite — a small robotic vehicle that can check the outside of a spacecraft for damage without an astronaut having to perform a spacewalk.

“Where this ties into the Proteus project is: Can we make satellites and spacecraft more intelligent and independent, capable of monitoring their state?” he said. “Once this is working for batteries, we can extend and work for other systems such as solar panels and hard drives.”

Being able to understand its own health and predict its future capabilities is clearly useful for a spacecraft that might have to operate for months or years without human intervention. The technology could also have applications down on Earth, in electric and autonomous vehicles, or in emergency equipment that is not often used, such as hospital generators.

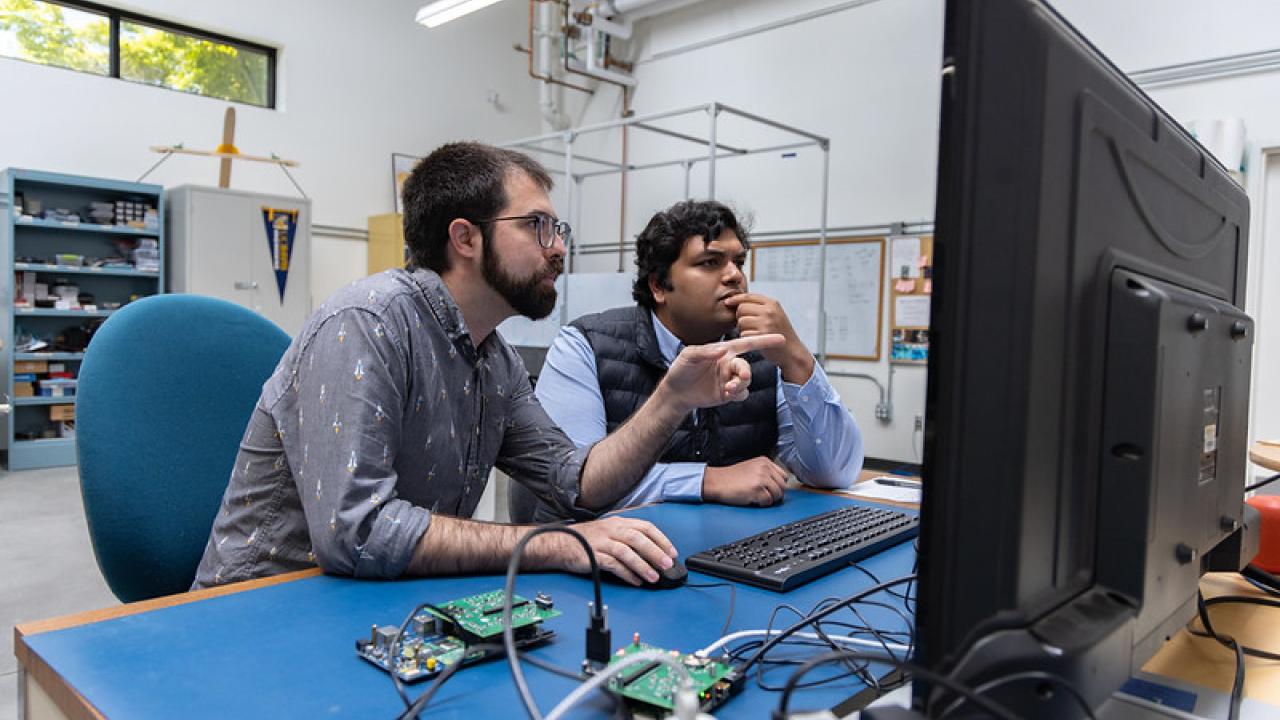

Ansha Prashanth, a master’s student in computer science, created the software that will run the device.

“During my bachelor’s studies, I worked on robotics projects, and I’ve always been interested in machine learning. When I learned about this satellite project, I was really drawn to the problem statement and its scope,” she said. “It was hands-on experience in working with real-world constraints. We had to deal with strict limits on size, data budgets, and timelines, which are quite different from the flexibility we have in academic research.

Fogelquist and Ayush Patnaik, a third-year Ph.D. student in Lin’s lab, developed algorithms to estimate how battery performance degrades over time.

“Batteries aren’t inherently very intelligent; they’re just cans of chemicals. So, algorithms give some insight into the health of the batteries,” Fogelquist said.

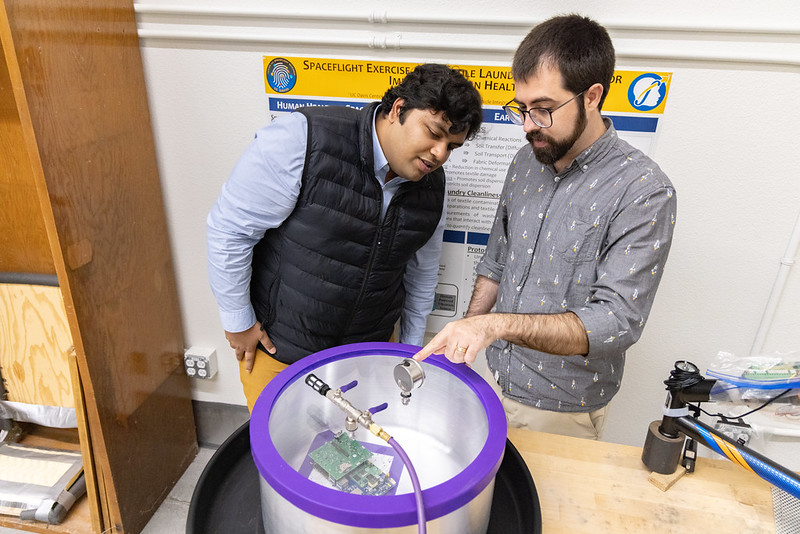

The team had to figure out how the battery would behave under different temperatures and in a vacuum. This thermal vacuum testing would typically require a six-figure facility with a lot of expensive equipment, Zufall said.

“We managed to do a modified version of that with hundreds of dollars of equipment, and just actually being able to replicate vacuum conditions with the cold and the hot conditions of space gave us a lot of insight into how this is going to perform when it gets there,” he said.

Charging at low temperatures (below 10 degrees Celsius) can lead to a phenomenon called lithium plating, Patnaik said.

“It is a lot in focus right now, because you degrade the battery really fast if this lithium plating phenomenon occurs,” he said.

“I think the fun challenge, the main challenge, was taking what we were doing in the lab, which is exercising these batteries under controlled conditions in a certain way and actually translating that to a physical board inside a spacecraft, following its own set of instructions,” Zufall said.

That involved miniaturizing their hardware, making it smaller and cheaper and writing software that could operate on its own for weeks or months.

“For me, the fun part was the challenge of making sure our data was safe and usable no matter what happened. Space is unpredictable, so the software needed to be designed to be smart enough to log efficiently, communicate and recover gracefully if anything failed,” Prashanth said.

Learning how to work across a team of different disciplines is a lasting result of the project.

“Spaceflight takes everything,” Robinson said.

“You have people from all different walks of life, and they don’t exactly talk the same language at first. There’s interpretation at first that leads to collaboration,” he said. “It’s not just for the success of this project or some specific project; it’s the people on the project who learn to do this and appreciate the value of it. That’s something they take with them for the rest of their lives.”

The satellite, which includes other payloads as well as the UC Davis experiment, is set to launch this October from Vandenberg Space Force Base.